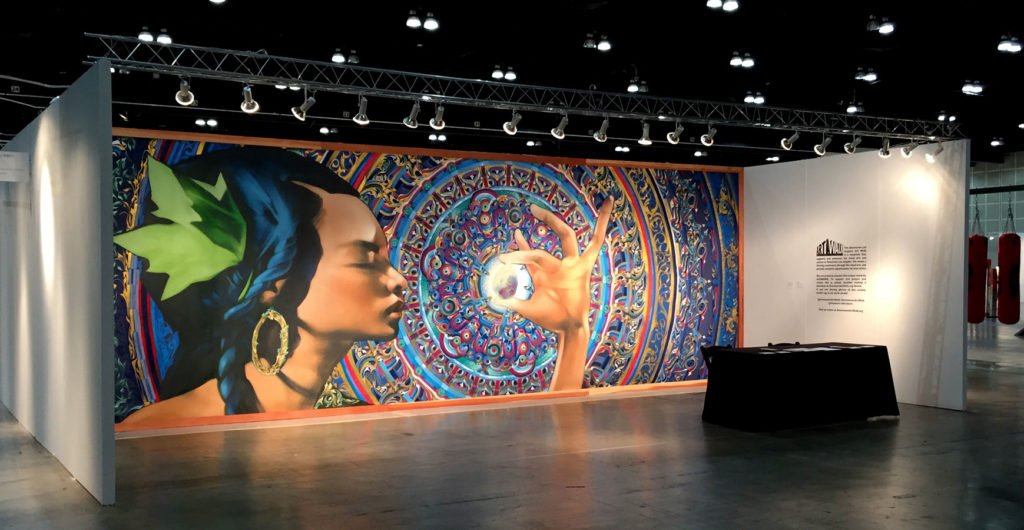

For graffiti/mural artist and painter Aiseborn, a love of letters and a gift for creating awe-inspiring patterns has propelled him to ever-greater heights out of tough beginnings. His 30 x 10-foot long mural at last year’s LA Art Show defined his remarkable vision. Titled Purity, the massive painting depicts a goddess or earth mother figure with a crystal in her hand that is radiating light, like an angelic beam. There is an ornate, circular aura behind her hand; a signature Aiseborn mandala rendered with breathtaking detail. “I wanted to give people a connection with something real versus a power or voice that can’t be seen,” he says.

The Downtown Los Angeles Art Walk had spawned the project in 2017 and were looking to bring a Downtown-based artist to the LA Art Show in 2018. Aiseborn fit the profile perfectly. “I had been inquiring with Art Walk about where my talents might be needed and was super excited when Curator Nat George and Executive Director Qathryn Brehm reached out to me,” says the artist. Despite the painting’s monumental size, it was an efficient operation thanks to the many friends who pitched in to help, including the owner of the Container Yard in the Arts District, who allowed the tarp and canvas to be spread through the space during production. “Yeah, I’ll never forget walking across this long piece of canvas with my socks on trying to be real strategic about where I was stepping. No small feat,” he says. The work was 60 percent spray paint and 40 percent brush paint, combining the artist’s talent for the two mediums.

“Manipulating spray paint on the ground isn’t easy, though, because of the air pressure quality,” he says. “Painting it was one level, but installing it was another. Fortunately, the Art Show had built out the space we needed.” The work was unique in scale and craftsmanship and drew wide attention. “Downtown Art Walk was really great in supporting the project and making sure we could do something that was memorable. It exceeded their expectations.”

Aiseborn’s interest in art began as a young child. “I never knew my mom and dad, and came through the foster care system. I dealt with years of homelessness. But I was lucky enough to see books with art.” These included books about the Renaissance and Victorian age, as well as sculpture and cathedrals. In grade school he’d doodle and draw from animation books. And from Hip Hop magazines, he’d create cartoons of rappers like Dr. Dre, Eminem and Lil Wayne in his own style. “Art seemed obtainable with no money down. Just pencil and paper, and I was getting real joy out of it. It wasn’t like a guitar or drum set. It wasn’t a ticket to Disneyland.”

By middle school he was sketching portraits and learning anatomical structure. A breakthrough came in high school when he spotted a classmate drawing cool letters with lots of color in a black book full of his sketches. “He gave me one of his sketches and I kept playing around with it. From there, I started to take an interest in what I was seeing on the street, and in the neighborhood.”

Photo by Nat George.

Aiseborn also started seeing other kids with similar black books. A ‘black book’ or ‘piece (masterpiece) book,’ helps to keep the graffiti community connected and organized, he explains. The sketches, doodles and hand styles are practice and prep. “You get a mental recognition of how your letters will work, and how to lay that down on the wall. You can figure out the scaling right away. All writers have a black book.”

Graffiti writers, he says, have to love letters. “You can’t just love drawing cartoons or animation. You have to love the letter forms. And those letter forms, they expand your imagination in ways the average artist can’t experience.” The best writers take the body of a letter and give it movement. “Artists who do letters are really graceful and look like they’re moving to a beat.” He adds, “They make it dance. It’s a sacred thing.”

Calligraphy also comes into play, he says, citing the influence of differing letter systems throughout the world. Old English letters, for example, often appeared in the 1990s and have since influenced the graffiti art form in Los Angeles. LA’s great cultural diversity has also been an influence. “In LA, there’s a merging of calligraphy and graffiti.”

The difference between graffiti art and mural art? “Graffiti art doesn’t have limitations on scale and can go from paper to a wall surface and just about anything else,” he explains. “Murals, both interior and exterior, must generally adhere to a surface that is already attached to a façade.” A mural can be installed on canvas, but it must be large scale. He adds, “Murals also have a tendency to be more legal than graffiti, but it depends upon a city’s ordinances.”

Aiseborn’s murals, he says, can be seen as a mandala or adinkrahene (West African symbol of greatness and leadership) or even something as simple as a medallion. “I discovered my own way of working. My own technique. It just felt right.”

Now an established artist, he can pick and choose commissions and volunteer projects. But like many graffiti artists he has faced financial hardship. “I think a lot of the time people forget that artists have to eat, and that they have family to care for,” he says. “Artists who have really harnessed their craft and created something that’s one of a kind deserve to be picky. If the people they’re working with want to nickel and dime them, then the artist has every right to back out.”

Volunteer work for local communities is an integral part of a graffiti artist’s practice. “For most of us, we started out in our community, and its where our hearts are coming from. We didn’t really think what it meant to get paid,” he explains.

“Whatever the subject matter may be, it’s getting the work out there for the neighborhood people to see and enjoy, and not having to deal with politics in between. We want to give them something uplifting that they can see in their daily life.”

Photo by Lucy Birmingham.

It was a few years back that Aiseborn was invited to join the influential, LA-based UTI Crew. The graffiti artist collective was formed in the 1980s, and now has about 200 members in cities across the U.S., Europe and Mexico. Members contribute to the Crew in their own way and collaborate with each other on different projects. Their purpose and reach have changed over the years. “Graffiti art can get a bad rap, but it’s more accepted in today’s world,” says Aiseborn. “The days of just putting letters on the wall is sort of over. Now it’s about the message we’re sending out, and the history that’s being told.”

Aiseborn’s own history includes dedicated time studying art at Los Angeles Community College. “Going to college and expanding the regimen I was creating for myself was important because my life after high school was very unstable,” he explains. Teaching art was in his thoughts. “Explaining certain principles and design elements in art would be very hard to learn without going to college. Getting familiar with the academic setting was also important if teaching art was ever to become a possibility.”

Dream fulfilled, Aiseborn is now bringing his life experience and artistic skills to young students at the William Grant Still Arts Center in Los Angeles. He is also transitioning into new creative territory. “I’m now expanding on my style in ways that have been attempted, but never done before.” For the people, a new inspiration.

++++++++++++++++++++++

Written by: Lucy Birmingham

Aiseborn: aiseborn.com